On Memorial Day 2022 in Granby, I had the honor to speak following the parade about the meaning of this day. The remarks are reprinted below. For a video of the speech, please click here. My speech is preceded by a beautiful rendition of our National Anthem by Greg O’Brien, at the 16:00 minute mark, and the speech begins at the 20:00 minute mark.

“Today, we remember and renew the legacy of Memorial Day, which was established in 1868 to pay tribute to individuals who have made the ultimate sacrifice in service to the United States, and to pay tribute to their families.

When deciding the subject of today’s speech, two fallen heroes who are memorialized with statues at the state Capitol caught my attention. At first, I thought that I would tell the story of only one of these men. During my research, I learned that they had both served in the same unit and both were killed by the British only six days apart, in New York City. My course of action was now clear: that I should tell both of their stories, which are deeply intertwined.

This Memorial Day, please join me in a trip back in time to 1776. We will remember two Connecticut Patriots who gave their lives for this country less than 3 months after its birth announcement. I will be brief on this hot day, but to make sure you’re listening, we are going to be interactive. I will ask you some questions.

The two of whom I am speaking today were citizen-Soldiers, members of their local militias. Like members of the National Guard and the Reserves today, they worked and lived in their communities, until called up for active military service.

The first name most of you will know. The second, I will be surprised if even one person knows his name. And please no looking it up on your phone!

Now, I am going to give you a few clues and then ask you to guess who I am referring to.

He worked as a school teacher in East Haddam and then in New London. By a show of hands, how many teachers and former teachers are here today?

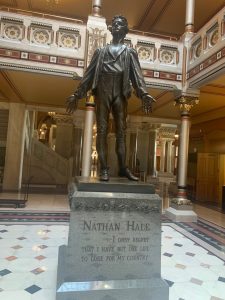

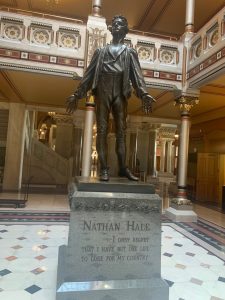

This patriot has a larger than life statue inside the state Capitol. He was designated the Connecticut State Hero in 1985. Before being hung as a spy, he is most known for his reported last words:

“I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

If you know who he is, then please shout it out.

You’re right, Nathan Hale is correct.

Hale grew up in Coventry, the son of Deacon Richard Hale and Elizabeth Strong. With his older brother Enoch, he attended Yale College, graduating with high honors at the age of 18.

Now for our second hero.

When he wasn’t performing military duties, he was a farmer. By a show of hands, how many farmers are here today?

I also learned that he was a selectman, like those who are beside me today.

Outside the state Capitol, there is a life-size statue of him standing with a saber in his right hand. Since 1995, the Military Intelligence Corps has presented an honorary award named after him, which I am wearing. While commanding the first intelligence unit in the Continental Army, he was mortally wounded in battle, his last words were reported to be:

“I do not value my life if we do but get the day.”

If you know who he is, then please shout it out.

(No one knew his name).

His name is Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Knowlton.

Knowlton moved with his family from Massachusetts to Andover, Connecticut when he was eight years old. He married Anna Keyes when he was 18 and she was 16. They had nine children.

Knowlton began military service at the age 15, in the French and Indian War, and fought in the Battle of Havana, Cuba at the age of 22. His family had a 400 acre farm, which is now the site of the June Norcross Webster Scout Reservation.

This Knowlton Award that I am wearing today was presented to me at Fort Huachuca, the home of Army intelligence, when I trained there. It is an award given to members of the Army Intelligence corps in order to promote esprit de corps. If not for this award, I would not have heard of Colonel Knowlton. I was certainly pleased when I first encountered his statue at the Capitol.

Let me now set the scene on how Hale and Knowlton gave their lives for their country in Manhattan in September of 1776.

General Washington’s successful siege of Boston ended when the British left that city on March 17, 1776. Knowlton had distinguished himself there at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Although Hale’s unit was also in Boston, there is no record of his role in any combat there.

Following the British withdrawal from Boston, Washington promptly shifted his attention to the defense of New York. He believed that it would be the next British objective, and he was right.

On the way to New York, Knowlton’s unit overnighted in his hometown of Ashford. There he saw his wife and young children for what would be the last time.

During July and August, the British conducted a huge buildup of troops and ships on and around Staten Island. They were preparing to take over the critical port city of New York.

Now General George Washington understood the value of good intelligence on the enemy. It leads to victories and to the saving of American lives.

Knowing the agility, valor, and resourcefulness that Knowlton demonstrated in Boston, Washington promoted him to Lieutenant Colonel on August 12th. Then he selected Knowlton to lead the first intelligence and reconnaissance unit of the Continental Army. The unit was to be 150 in number and to be known as the Rangers.

The majority were from Connecticut, the rest from other New England states. Many were hand-picked by Colonel Knowlton, including his older brother Daniel and his sixteen-year old son Frederick, as well as Captain Nathan Hale. The unit became known as Knowlton’s Rangers, and they reported directly to General Washington.

The Battle of Long Island, at Brooklyn, took place the last week of August. 20,000 British troops faced half as many Americans. In number of troops engaged, it was to be the largest battle of the American Revolution.

General Howe’s troops outnumbered and outmaneuvered Washington’s troops. With defeat inevitable, Washington secretly withdrew to Harlem by boats in the dead of night on August 29.

For the next encounter, Washington needed better intelligence on the British forces. Colonel Knowlton asked among his ranks for a volunteer to spy behind enemy lines. Only Nathan Hale volunteered, yearning to contribute to the American cause, despite the dire risk. Now a spy loses the protections of the customs of war, and is subject to execution if captured, and he knew this. Hale embarked on his secret mission on September 12th.

Battle lines shifted now to Harlem. On September 16th, Knowlton’s Rangers were tasked with scouting British lines around Harlem Heights. During this action, Knowlton was mortally wounded in the back, and died that day at the age of 35. He was buried with military honors in an unmarked grave between 135th and 136th streets in New York City.

Around this time, Nathan Hale, posing as a Dutch teacher looking for work, and carrying his Yale diploma with his actual name on it, crossed Long Island Sound from Norwalk by sloop and landed near Huntington, NY. Little is known of Hale’s actions over the nine days of his mission. There are conflicting accounts on how his mission was compromised. He was captured on September 21st.

Hale was ordered executed by hanging the next day. On the morning before he was hung, he wrote two letters: one to his brother Enoch, and the other to COL Knowlton, who had already been killed, unbeknownst to him.

Nathan Hale was hung at 11 a.m. on September 22, 1776. He died for his country at the young age of 21. His body was left hanging for several days, and he was buried in an unmarked grave.

Washington ultimately decided to cut his losses in New York and withdraw to New Jersey. But the remaining Rangers stayed behind near Harlem to guard outposts. They lasted until November 16th when the troops at Fort Washington surrendered. Most of those rangers that survived until then were captured that day.

On Memorial Day, we honor men like Nathan Hale and Thomas Knowlton, and all those who came after them, who gave their lives for their country. We also honor their families who suffered the deepest loss.

We ask ourselves what motivated the selfless service of Knowlton and Hale and the Rangers? Were their sacrifices in vain? When Hale and Knowlton first joined the American Revolution in 1775, America was just an idea, or a vision, of how people should live in freedom with a representative government. By the time that they were killed fighting for that freedom, that vision was put into the words of the Declaration of Independence:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Now the Declaration is an ideal, that we are to aspire to but have not always lived up to. In pursuit of living up to the promise of our birth certificate, we’ve endured severe growing pains, including a devastating Civil War. But the Declaration created an aspirational standard, that is worth attaining. This requires continual effort and vigilance.

Whether the ultimate sacrifices made by Nathan Hale and Thomas Knowlton, and all those that have followed, are in vain, is ultimately up to us. The lives lost are not in vain if all of us here re-embrace our founding principles and instill a love of them in our children. You are doing that by being here today.

God blessed America. Let us not take that blessing for granted, lest we lose it forever.